Jean-Michel Basquiat IN THE WINGS

“Jean-Michel began to incorporate the names of these songs and the linear notes of the records, and mesh those words with images in his painting…He immortalized those records in a way that blended with his style and was very much a part of where he was coming from. But always with a twist and sense of humor.” (Fred Braithwaite, “Jean-Michel as Told by Fred Braithwait a.k.a. Fab 5 Freddy, An interview by Ingrid Sischy,” in Exh. Cat., Malaga, Palacio Episcopal de Malaga, Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1996, p. 155)

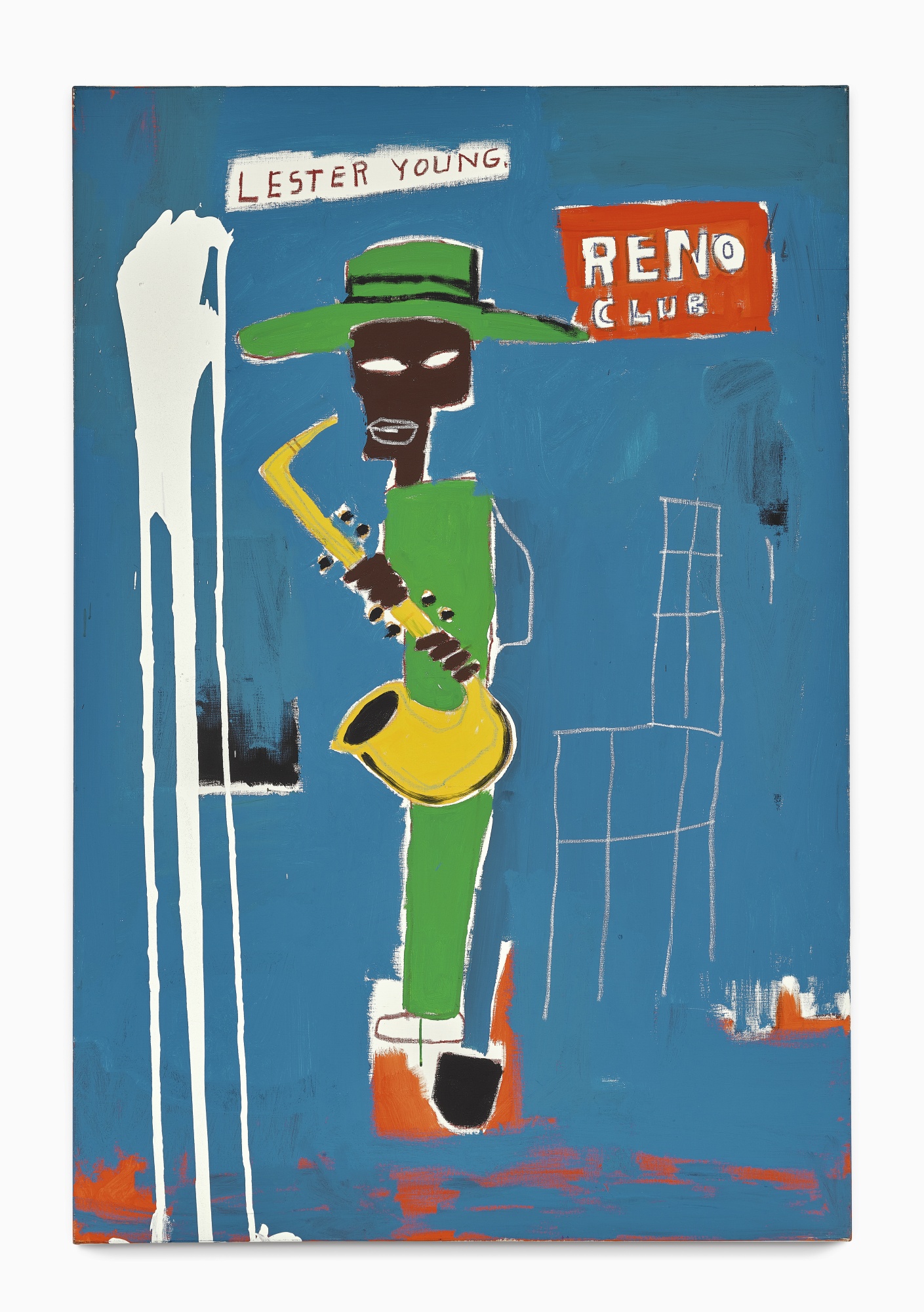

Painted in the crucial moment of 1986, just two years before his untimely death, Jean Michel Basquiat’s In the Wings is undoubtedly one of the most charismatic cultural portraits of his entire oeuvre. Adding to the limited number of important paintings that he dedicated to the greatest jazz legends of the Twentieth Century, here Basquiat enshrines the image of Lester Young – arguably the most influential and innovative saxophonists of all time – and creates a highly personal, devotional icon for posterity. Beyond paying homage to his musical idol, Basquiat instigates a cross-generational synthesis of artistic volition as the fluidly improvisatory tones of Young’s radical jazz are given a perfect visual counterpart in the painter’s unique gestural flare. Bearing a relatively pared-down composition, an enigmatic blue background and by focusing on a single African-American figure, In the Wings is stylistically emblematic of the important set of works created in the final years of Basquiat’s career in which he focused more heavily on Black subjects. By inducting Lester Young into his great pantheon of Black cultural icons, Basquiat seeks to reshape narratives on African American culture, whilst simultaneously positioning himself as contributor to its great legacy. Having acknowledged himself as a relative rarity as a Black artist within a racially homogenous art world, through In the Wings Basquiat destabilizes the canon of cultural history by inserting Black consciousness at its forefront and chiefly positioning himself as its visionary narrator.

From famous athletes such as Sugar Ray Robinson, Cassius Clay, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, to political figures including Malcolm X and Marcus Garvey, Basquiat’s oeuvre is punctuated by emphatic references to ground-breaking African American figures of the 20thcentury. Reverentially valorizing their successes in the face of staunch adversity and extreme racial prejudice, the historic development of American jazz music became Basquiat’s third arena in which to explore the rich and influential products of Black culture. Such as in the 1983 work Horn Players, now in the collection of the Broad Museum in Los Angeles, from early in his career Basquiat celebrated what Bell Hooks has described as "the innovative power of black male jazz musicians, whom he reveres as creative father figures," later proceeding to depict significant musicians such as Charlie Parker, Dizzie Gillespie, Ben Webster, Duke Ellington, Max Roach, Billie Holliday and Lester Young. (Bell Hooks, 'Altars of Sacrifice: Re-membering Basquiat' in Outlaw Culture: Resisting Representations, New York, 1994, p. 35) Painted in the same year and bearing the same blue backdrop as the present work, King Zulu (Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art) is another work also dedicated to a founding feather of American Jazz, Louis Armstrong.

From the 1950s, as a predominately African American Art form, Be-bop Jazz revolutionized the trajectory of music by privileging a highly expressive and improvised approach that finds a replete parallel in Basquiat’s painterly freedom. With individualism and experimentation at the heart of jazz music, each of Basquiat’s jazz heroes maintained a distinctive vocal or musical style, making unique artistic contributions to the development of the genre. Starting as an innovative member of Count Basie's band in Kansas City in the mid 1930s, Lester Young is one such figure who redefined jazz through his sensual refinement of Swing music. In the present work, Basquiat ultimately mirrors the relaxed tone and sophisticated harmonies that set Young’s music apart from his contemporaries in the supreme formal balance that also retains a sense of energetic improvisation. Compared to the densely frenetic compositions of the early 1980s, here we see a wise and confident Basquiat carefully selecting references and techniques – marrying style and content – to offer a highly particular vignette.

Young was well known for the unorthodox manner in which he positioned his saxophone as he played. Emerging from a brilliant blue backdrop, Basquiat privileges this detail with the contrasting yellow glare of the centralized instrument. Grasped by the dandyishly styled Young in a vibrant green suit and wide-brimmed hat, the charismatic musician is spot-lit and center stage in the composition. Surrounded by the stupefying abstract rhythms of the artist’s brush, a visceral cascade of gestural white paint down the left edge of the picture provides a synesthetic evocation of free flowing sound. Yet, whilst the canvas chimes with the exuberance of a live performance, Basquiat’s use of text and his characteristic insistence on two-dimensional depiction seems to intimate a promotional poster or perhaps a record cover, as his immediate frame of reference. Having died in 1959, Basquiat’s evocation of the “Reno Club” refers to an original live recording made there in Kansas city in 1936; one of the many Jazz records that provided an inspirational score against which his distinct subjective visions were created. Basquiat’s expedient rise to success had come through his fresh presentation of a diverse mélange of cultural influences, from graffiti tags to comic books and even food packaging. Here he simplified his unique symbolic lexicon to focus on one favored moment in the history of jazz.

Whilst Lester Young was known for having popularized much of the jazz ‘hipster jargon’ associated with the genre, here Basquiat evades his own characteristically ambiguous use of words, privileging instead their ability to designate the specific moment. This open stage allows Basquiat to bathe his central icon in a fittingly lyrical abstraction that shows the full range of his transcendent technique as both a painter and draughtsman. As Robert Farris Thompson describes, Basquiat consciously enters into a nuanced dialogue with his painterly predecessors: "Basquiat himself did not parody Abstract Expressionism, as Pop Masters sometimes did. As he fused his sources, his mood was more complex: humour, play, mastery, and stylistic companionship. He brought into being first-generation (Kline) and second-generation (Twombly) Abstract Expressionist citations and mixed them up amiably with cartoon, graffitero, and other styles." (Robert Farris Thompson, 'Royalty, Heroism, and the Streets: The Art of Jean-Michel Basquiat' in Exh. Cat., New York, Whitney Museum of American Art, Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1992, p. 36) Whilst the luscious drips of free-flung white provide a nod to Jackson Pollock, the whimsically minimalist scrawl of the white squares that suggest a chair seem to toy with the authority of the minimalist grid, promulgated by Sol LeWitt, Donald Judd and Agnes Martin. Invigorating the background with a static red that demarcates form and bleeds through in the manner of both Robert Motherwell and Clyfford Still, Basquiat usurps the authoritarian schools of painting that dominated American art until his arrival upon the New York scene, whilst responding to the revolutionary aural experience of Young’s music.

Crucially, Basquiat’s highly abstracted treatment of Young’s face brings to light the intersection of race, representation and culture that underscore the painting. Composed of a rich mahogany brown, the highly stylized eyes and naively emphasized lips take a dually provocative role by recalling both the resounding influence of African art on modern masters such as Picasso, as well as the unsettling aesthetics of minstrelsy and the archaic racial stereotypes that once permeated American visual culture. As surmised by cultural theorist Dick Hebidge "… in the reduction of line into its strongest, most primary inscriptions, in that peeling of the skin back to the bone, Basquiat did us all a service by uncovering (and recapitulating) the history of his own construction as a black American male." (Dick Hebidge, "Welcome to the Terrordome: Jean-Michel Basquiat and the Dark Side of Hybridity," in Exh. Cat., New York, Whitney Museum of American Art, Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1993, p. 65) In his tribute to Lester Young, on one level Basquiat gives aesthetic form to the revolutionary rhythms of jazz as a means of celebrating the legacy of Black culture and the historic achievements of Black artists. However, in also considering African American identity at the intersection of personal experience and a set of performative masks, he has immortalized his own subjectivity within the canon of cultural consciousness.